CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT SUITE

Customer Referral Value

Among the many benefits of fostering high customer satisfaction is the likelihood that the satisfied customers will then attract new customers via positive Word-of-Mouth (WOM) and referrals. Insofar as the profits generated by these new customers can be attributed to the original referring customer, it becomes evident that customers are capable of generating value both directly and indirectly (Kumar, V. (2008); Kumar, V. (2013)).

One of these indirect values is captured by Customer Referral Value (CRV). Compared to CLV, CRV requires a more rigorous, time-intensive methodology, as it must be determined how many referrals a customer will make when directly prompted, usually through some incentive offered by the firm (Kumar, Petersen, and Leone, (2007)). Only the referrals made up to a year after the original incentive can be attributed to that incentive. Moreover, it must be determined which of the newly referred customers would have become customers eventually, without the referral (type-one referrals), and which would not have become customers without the referral (type-two referrals). The respective values of these two groups of referred customers are added together to arrive at CRV.

CRV helps determine which customers should be targeted for WOM and referral campaigns. Many firms go the easy route, relying on the CLV metric to make such determinations. But CRV and CLV are not interchangeable – customers who rate highly on one are not likely to rank highly on the other. Firms that compute CRV will launch more successful referral campaigns and, therefore, make better investments in their customers. But this is not to diminish the importance of CLV. Firms that compute both values will have greater leverage in targeting the right campaigns to the right customers.

To show the impact of measuring and managing CLV and CRV simultaneously, a field study was conducted with a financial services firm to see the benefits of measuring and managing CLV and CRV simultaneously (Kumar, Petersen, and Leone, (2010)).

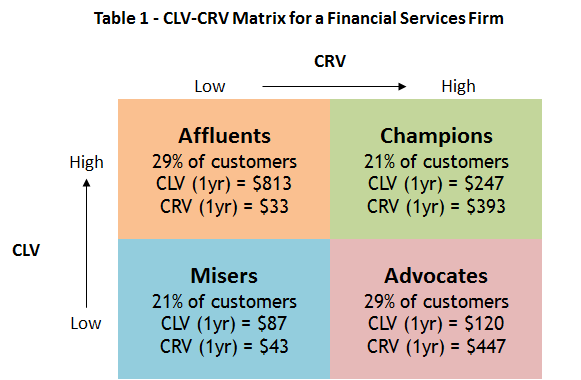

For the purpose of the field study, a test group and a control group of 9,900 customers each were considered. For each of the groups, CLV and CRV were measured. Based on these two values, the customers in both groups were divided into four cells of a 2X2 matrix. The cells were segmented on the following basis – high CLV/high CRV, high CLV/low CRV, low CLV/high CRV, and low CLV/low CRV. The cutoff points for the four segments were determined based on the median value for both the CLV and CRV measures. Table 1 summarizes these results.

“Affluents”, or the high CLV/low CRV customers, purchase a lot of products and services for themselves, but they do not refer many new customers to buy products and services.

“Misers”, or the low CLV/low CRV customers, do not purchase much or refer many new customers. Their low purchase behavior may be due to frequent brand switching, small SOW, or they might be waiting to find out from others whether the product is worth purchasing.

“Advocates”, or the low CLV/high CRV customers, do not exhibit a high purchase behavior for themselves. However, they are actively involved in talking about the product to other customers and encourage them to buy products.

“Champions”, or the high CLV/high CRV customers, are more likely to buy more products/services from the company and talk more about them to other customers.

To understand the true value of treating customers differently, the financial services firm initiated three different campaigns over the course of one year in an effort to migrate customers from low CLV/CRV cells to high CLV/CRV cells. These campaigns were administered to the sample customers from the test group. The control sample did not receive any of these targeted marketing communications. The goal of each of the campaigns was to migrate customers toward one of the other three cells (“Affluents”, “Advocates”, or “Champions”), depending on whether the campaign increased their CLV, their CRV, or both.

The study tracked the three segments individually and monitored their performance. At the end of one year, the number of customers in the “Misers” segment decreased from 21% to 9%. Of the 12% who migrated to other segments, 4% of the customers went to the “Affluents”, “Champions” and “Advocates” segments each. The gains from this migration were also substantial. The average CLV increase (due to the migration exercise) in the “Affluents”, “Champions” and “Advocates” segments were 185%, 67% and 157% respectively. Similarly, the average CRV increase in the “Champions” segment was 267%. It is therefore clear from these findings that the strategy was successful in not only migrating customers toward better cells, but also in moving these customers to cells that have significantly higher CLV, CRV, or both.

References

Kumar, V., J. Andrew Petersen and Robert P. Leone (2007), “How Valuable is the Word of Mouth?”, Harvard Business Review, (October), pp. 139 – 146.

Kumar, V. (2008), Managing Customers for Profit: Strategies to Increase Profits and Build Loyalty. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing.

Kumar, V., J Andrew Petersen, and Robert P Leone (2010), “Driving profitability by encouraging customer referrals: who, when, and how,” Journal of Marketing, 74 (5), 1-17.

Kumar, V. (2013), Profitable Customer Engagement: Concept, Metrics, and Strategies. New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.